The History of Emmanuel Episcopal Church Orcas Island, Washington

To view/download a copy of Emmanuel’s History in pdf format, click here.

Click on the arrows below to read each section:

Prehistory to 1883: Natives, hunters, and pioneers enjoy the natural abundance of Orcas Island

For at least ten thousand years before the appearance of whites, Coast Salish native peoples hunted, fished, and gathered the islands of what we now call the San Juan Archipelago. Sadly, their tribal names are mostly familiar to us as place names—the Salish Sea, Lummi Island, the Saanich Peninsula, the Samish River. During the summer months, the Salish made seasonal camps in the islands, where they fished, collected shellfish, dug roots, picked berries, and hunted deer and birds. At low tide, they walked the Orcas shoreline, gathering mussels, oysters, sea cucumbers, chitons, barnacles, scallops, sea urchins. Using sticks, they dug clams. Carrying baskets, they waded through the shallows to collect crabs. On the routes of migrating salmon, they set up elaborate reef nets. Some of the shellfish they ate raw, but the larger portion they steamed in pits or tossed on fires to roast, and, thinking ahead to the winter months, they dried much of the salmon on racks in the sun. Knowledge and ownership of clam digging and fishing sites was passed through families from generation to generation.

Spanish and English explorers began to map the islands in the 18th century–“Orcas” is a shortened form of Horcasitas, after Juan Vicente de Guemes Padilla Horcasitas y Aguayo, the Viceroy of Mexico who sent an expedition to the Northwest in 1791–but whites did not settle on Orcas until the early 1850’s,when two hunters from the Hudson’s Bay Company on Vancouver Island settled in Deer Harbor, on the west side of the island, and married native women. The deer hunters were followed by hunters of a different sort, white men travelling to and from the goldfields of the Fraser River in British Columbia. Stopping in the islands, they were attracted by the abundant natural resources that had sustained native peoples for millennia.

Due to the difficulty of transporting goods to and from the islands, the first economic activities on Orcas were mainly trade and barter, followed by commercial enterprises, including fishing, logging, and the mining and smelting of lime. Photos from the early period of white settlement show a frontier scene of log cabins and pioneer people. Later, small settlements, with buildings constructed from milled lumber, developed around the docks from which the lime, fish, and logs were shipped. Post offices still mark four of these communities, at Orcas Landing, Deer Harbor, Doe Bay, and Eastsound.

In 1883, into the frontier community of Eastsound, entered the most unlikely couple– European immigrants of privileged backgrounds, and so begins the history of Emmanuel Episcopal Church.

1883: Emmanuel Episcopal begins with a romance and a dream

The romance began across the sea, between Sidney Robert Spenser Gray, a red-whiskered Englishman and product of Eton and Oxford, and Alma Mecklenberg, daughter of the reigning duke of Mecklenberg-Schwerin, which had recently become part of the German state. The families of both Gray and Mecklenberg were set against the love affair: the Mecklenbergs thought the alliance below their status, while the Grays were horrified at the idea of their son marrying a foreigner, particularly a German. Consequently, when the marriage occurred without parental consent, both bride and groom were disinherited, and the couple sought a new life on a new continent, sustained by funds Gray had managed to deposit under his own name.

Barely thirty years old, and filled with energy and vision, Gray and Alma arrived on Orcas Island in 1883, where Gray was authorized by the Diocese in Seattle to serve as a lay missionary for the Episcopal Church. An early church historian reported that “by the time Gray arrived, the island had passed through the hunter and trapper stage, the Indian wars over fishing grounds had ended, and smuggling had become less easy and more lucrative.” The landscape of the island, with its forests and meadows, hills and valleys, struck a familiar note in Gray’s heart, and it was not long before he envisioned a picturesque village modeled on those of his native England, including thriving businesses and farms, separate schools for girls and boys, and, as the hub of the community, an English country church. From this dream, Emmanuel Episcopal Church came into being.

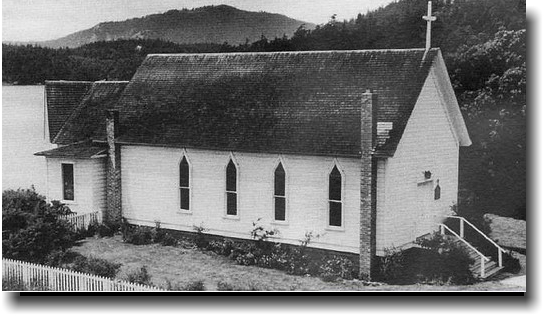

1885: Church built on site originally intended for saloon.

Emmanuel Church was built on property donated to the congregation by Charles Shattuck, a mule- skinner from Michigan who had gone to California as a “Forty-niner.” Shattuck had also mined along the Fraser River, and in the course of his trips up and down the Puget Sound, had rowed to Orcas Island to investigate the hunting. When he found deer in abundance, he pitched a tent on the beach and sold hides and meat to traders from Victoria. Later he brought in a boatload of lumber and built a cabin, married an Indian woman, built a store, and became Eastsound’s first Postmaster.

LuLu Kimple, whose descendents still live on the island, remembers that, originally, the site of the church had been intended for a saloon, “but the church women got together and protested so strongly that the man was scared and gave up on his project after having cleared the lot and put in the foundation for the building. My mother was a leader in this fight and I remember the excitement very well.” With Shattuck’s gift of land, the congregation set about building the church to Gray’s design. Michael Donahue constructed the building, aided by carpenter Ed King and local workmen. Writing in 1945, Nova Langell credits the solid workmanship of the church to Donahue, “just as its fine lines and clean, simple plan were due to the Reverend Sidney R. S. Gray.”

1885-1891: Gray’s dream bears real fruit and attracts European immigrants to island

Sidney Gray’s vision extended far beyond two Sunday sermons and his parish responsibilities. Discovering that the soil and climate of Orcas Island were admirably suited to the growing of fruit– particularly apples, plums, pears, and strawberries– Gray persuaded Puget Sound financiers to form the Orcas Island Fruit Company. Island residents rushed to clear land and plant fruit trees. As island businesses thrived, Gray developed plans for the ideal “Village de Haro,” located on Madrona Point, and began raising money to fund private schools for both boys and girls. He dispatched numerous letters to England singing the praises of Orcas Island, and, before long, English and Scottish immigrants arrived to buy land and take their places in the new community. In his journal from that era, James Francis Tulloch, a pioneer and the first church treasurer, somewhat sardonically describes Gray “as an extremely likable and gentlemanly fellow who could talk a bird off a bush…His great mistake was in not becoming a real estate agent.” A more complimentary description reads, “He was red-headed, wore whiskers, and was filled with energy, vision and devotion. A most unusual man by any standards.”

1891-1893: Bank failures end Gray’s dreams

Then as now, the fortunes of Orcas Island were subject to influences far beyond the island. After Argentina defaulted on bonds held by British banks, causing their failure, a ripple effect led to a panic among American banks. Ultimately every bank in the Puget Sound area was affected by the European failures and began to call in notes. Sidney Gray’s dream of a model English village was among the casualties. The people of Orcas, finding themselves heavily in debt and with no resources but their land and energy, returned to the economics of an earlier period: bartering, trading, and growing their own food. In 1893, his dream shattered, Reverend Gray resigned as vicar and accepted a call to the Midwest, where he remained for the rest of his life.

During the six years the island enjoyed a thriving fruit industry, the church was the center of community activity. Langell writes, “Sunday services were attended by so many that the little church was often crowded. The music was good, the sermons vigorous and instructive, and the ritual was conducted with great solemnity.” After the crisis of 1891, however, both the island population and church membership declined. In May, 1893, a letter by Richard H. Geoghegan describes a “Poverty Social” hosted by the Saint Agnes Guild: “The most enthusiastic citizens can hardly claim that the social whirl is particularly dizzying at any time in their city, but any semi-occasional spasm of excitement that does pass over the place may usually be traced to the church debt as its starting place.” Geoghegan wrote that one guest arrived in a costume of gunny sacks and salt bags, a boot on one foot and on the other a shoe with “hygienic ventilation around the toes.”

1895-1904: The “rowing Vicar,” John William Dickson, tends flocks on Shaw and Orcas Islands

After Gray’s departure, the Reverend John William Dickson was appointed Vicar, serving from 1895 to 1904. Dickson commuted to Orcas from Shaw Island, where had settled, by rowing to Orcas Landing, towing behind him a scow onto which he had tied his horse, which he then saddled and rode the eight miles to services in Eastsound and then onto Westsound, the residents of which had constructed a church in 1895. Dickson then rode and rowed the horse and himself back to Shaw for evening services at the small parish there. Parishoner Harding Gow remembered the Reverend Mr. Dickson as coming “nearest to deserving the name of ‘Saint’ of any man I ever met. His patience was infinite and his resignation and sense of humor are well illustrated by a story that was told of him: [Dickson] had saved for a long time to buy a cow, and at last he had the funds in hand and had started for the mainland to select the animal. The boat met with rough water and the Reverend gentleman got seasick—and his false teeth followed his lunch overboard. Sick as he was he managed to muster up a wry smile and say, ‘Well, there went my cow.’”

1904-1928: Congregation and the church building survive uncertain times

After the panic of 1907, the fortunes of Orcas Island and Eastsound declined further. Irrigation was introduced to eastern Washington, making possible the planting of large-scale orchards there; as well, the development of railroads and improved roads made it cheaper to transport fruit by land, marking the end of the fruit industry on Orcas. When Father Dickson left in 1904, the church stood empty for twelve years, without a vicar. In 1916, the Diocese of Spokane was reorganized and the newly retired Archdeacon Henry J. Purdue came to Orcas Island, where he was persuaded to serve as vicar. After twelve years on the island, Purdue retired a second time, and again the church stood empty.

1928-1954: Commuting ministers lead worship; St. Agnes Guild rescues deteriorating church building

Determined not to let the church fall into disrepair, the ladies of the St. Agnes’ Guild, led by Mrs. Harding Gow and Miss Jessie Templin, moved into action, raising enough money with bazaars, teas, recitals, and other activities to re-shingle the church building in 1932. In 1939 they were given charge of the church property and began to look into acquiring land for a parish hall. In 1940, the Guild organized its first major sale for the purpose of raising money to repair the church and establish a building fund. For over 70 years–to the present day–the guild’s annual “Market Day” has been a highlight of the Orcas summer. An article in a 1947 issue of Orcas Islander describes the appeal: “For years it has been the leading event of its kind on the island. It affords a pleasant meeting place where one can greet old friends, have a cup of delicious tea, and perhaps buy one or several articles that are not found in stores.” In 1948, “the gross receipts for the sale totaled the amazing sum of more than seven hundred dollars,” collected from booths including the Green Grocery, Costume Jewelry, White Elephants, Fancy Work, Aprons, Basement Bargains, and the men’s table, The Dog House.

In 1946, Mr. Fred Meyer, owner of the Outlook Inn, donated property west of the church for the parish hall. A 1947 newspaper headline reads “Hope strong for a parish house soon,” and goes on to report that “emphasis was laid on the necessity of a parish house that can accommodate youth activities. The island’s greatest need is for something for our young people to do.” In 1948, guild members began soliciting plans. Although some in the parish were opposed to attaching the hall to the church, feeling that its classic lines would be compromised, the hall was completed and dedicated in 1951.

After the Second World War, the island community began to grow again, “adopted by retired businessmen, resort owners, and year-around vacationists.” A charming letter from the Bishop in Olympia, in advance of a parish visit, describes the appeal of the island: “Perhaps we can get a small cottage there, starting say on Saturday and running over Monday because it is certain that if we come up there we shall want to do some fishing on the day following the service.”

Between 1942 and 1953, the church was served by commuting clergymen from the mainland, initially by the Rev. Oliver Drew Smith of Mt. Vernon, followed by the Reverend George Pratt, of Abbotsford, British Columbia. During Rev. Pratt’s ministry, electricity was installed in the church. In 1954, Father Johnson West, who had been a Navy pilot in WWII, became vicar of the San Juan Islands, but two years later he was commissioned as an Air Force Chaplain and did not return to lead the congregation until 1974, at the conclusion of the Vietnam War.

1956-1968: Emmanuel Parish is served by Father Glion Benson, the “Seagoing Vicar” of the San Juan Islands

With the departure of Rev. West, Father Glion Bensen was appointed Vicar, assigned to serve parishes throughout the archipelago. Then as now, however, ferry service between the islands was infrequent and, occasionally, uncertain, so in 1957, the Daughters of the King, aware of Father Benson’s need for adequate transportation, raised $2,000 to buy a converted Navy whaleboat, which Father Benson christened The Royal Cross (aka The Rugged Cross and Holy Smoke).

Benson had been a Navy seaman during World War I, and following discharge had worked as an oiler and engineer on a number of merchant marine vessels, so he was particularly well suited to the island ministry. Accompanied often by Mother Benson, he spent many hours chugging to and from services on San Juan and Lopez Islands and making parish calls on other islands. It was Father Benson who erected the ship’s mast flagpole that still stands in the churchyard, from which he flew signal flags during services. Visiting boaters were often surprised to see coded messages flying from the yardarms:

U: You are standing in danger (rocky coast). RSX: Is all well with you? RSV: Where are you bound? BCN: We will not abandon you.

Meanwhile, Mother Benson worked tirelessly to make the churchyard worthy of gardens in her native England. The living cross of white crocuses, near the bell tower, was first planted by the Bensons.

1968-1984: Father Benson retires after second heart attack; Rev Johnson West returns to Emmanuel Episcopal; the parish acquires Benson Hall

In 1958, while lighting the parish hall furnace, Father Benson suffered a heart attack. Ten years later, after a second, serious, heart attack, Mother Benson insisted that he give up The Royal Cross; that same year, Benson retired from the ministry. However, as a self-titled “God’s recycled altar boy,” Father Benson continued to lead services on Orcas and Lopez Islands until 1974,in support of Father Ted Leche, the newly appointed Vicar.

The year 1968 also saw construction of a new porch, entryway, and freestanding bell tower at the church, the latter housing a 300-pound bell cast in Holland. The beautiful Agnus Dei (Lamb of God) window above the entrance was designed by Charles J. Connick of Boston, inspired by medieval windows in England and France. Of the new front porch, a local newsman wrote, “Formerly, the doors of the church had opened into the back of the sanctuary–and the backs of worshippers as well, which has always been an inconvenience in inclement weather. (Yes, even Orcas Island has that kind of weather, now and then…).”

In 1974, the Reverend Johnson West returned to serve the island as Vicar. During the next ten years, “Padre” West, as he enjoyed being called, was instrumental in expanding the church property eastward along the waterfront, acquiring a building that, since its construction in 1930, had housed various businesses, including a grocery store, electrical and upholstery shops, and, as tourism increased after the war, a gift store. Renamed Benson Hall after the beloved, sea-going vicar, the building housed church offices, Sunday school classrooms, and meeting rooms used by both church and community. In a closet in Benson Hall, Padre West began the Orcas Island Food Bank, which, thirty-five years later, thrives in a new building on property leased for $1 a year from the Orcas Island Community Church, a short walk away. Father West was also instrumental in the church acquiring parish status in 1979. Father West’s widow, June, and their children and grandchildren continue as active members of the parish.

1985 to 1996: Emmanuel Episcopal Church celebrates its centennial, the church building is placed on the National Registry of Historic Places, and parishioners make significant improvements to the campus

Emmanuel Episcopal Church, the second oldest church in the San Juan Islands, celebrated its centennial on December 14, 1985. Nine years later, in 1994, during the tenure of Reverend Patterson Keller, the church building was placed on National Registry of Historic places. In 1990, the church acquired a large pipe organ from the Bond Company in Portland, Oregon, at which Music Director Marianne Lewis, leads the congregation in music. It is the second largest pipe organ in the islands, exceeded by only that of the Moran Mansion at the Rosario Resort. In 1995, new carpeting and pews improved the nave.

In 1996, after supporting the church building for 111 years, the original foundation was replaced. Under the church, workers found the petrified body of otter, and it was rumored that the ashes of deceased parishioners also lay there; however, no evidence was found. However, the contractor did report that the reason the foundation had lasted so long was that the original carpenters had used boat-building joinery and created a ventilation system for the walls and supporting beams that kept the wood from rot.

1996 also saw the creation of the long, mixed border just inside the picket fence, lovingly cared for by the “Garden Gang” and dedicated to the memory of Dale Pederson, leading planner of the Main Street Improvement and Beautification Project. The lawn and Memorial Garden are sites of unmarked graves from as far back as the 1880’s, and more recently, the burial sites of ashes marked by small plaques. The stone Columbarium at the water’s edge also holds cremated remains.

1996 to 2003: Benson Hall is sold and barged to Lopez Island; the church builds a new Parish Hall under the leadership of Rector Craig West

In the early morning hours of Valentine’s Day, 2002, at high tide, nearly 200 islanders braved the freezing weather to watch workmen hoist Benson Hall onto a barge for a voyage to its new home on Lopez Island, where it was returned to its original use as retail and office space. Under the leadership of Rector Craig West, work on a new parish hall began immediately. Dedicated in 2003, the Parish Hall, like Benson Hall before it, is continuously used by both the church and the community for fellowship, worship, learning, lectures, meetings, and celebrations. The ceiling echoes the beautiful lines and woodwork of the original church, and the view from the picture windows onto East Sound and the surrounding mountains is a reminder of nature’s exquisite handiwork.

Craig West, Rector from 1996 to 2003, is also remembered for his gifts in pastoral care and his willingness to explore multiple spiritual perspectives. He often began his sermons by referring to the scriptural lessons, asking, “So what did you hear?” After leaving Emmanuel in 2003, Pastor West became a priest on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

2007 to 2013: Bishop Craig B. Anderson leads the church to increased membership and attendance; labyrinth dedicated on east lawn.

Bishop Craig B. Anderson, came to Emmanuel in 2007, upon retirement from a long career in education and ministry, including nine years as the Bishop of South Dakota. Under Anderson’s leadership, Emmanuel Episcopal experienced growth in membership and attendance. Upon his retirement, in May, 2013, Bishop Anderson continues his ministry as assisting bishop in the Diocese of Olympia. The Reverends Kate Kinney and Wray MacKay, retired priests from the Diocese of Olympia, are serving as interim Co-Rectors as the parish searches a new rector.

In late fall of 2010, leaders from the Samish Indian Tribe, for whom the Emmanuel Episcopal site is also sacred, led the congregation in blessing the east lawn of the church, where a permanent, stone labyrinth was dedicated in May of 2011. Modeled after the labyrinth of Chartres, France, the labyrinth is a gift to the community from the church, intended for contemplative use by residents and visitors alike.

Besides contemplation and remembrance, the church lawn is also a popular site for celebration. On Wednesdays in July and August, residents and visitors enjoy noontime Brown Bag concerts, and on summer evenings, passers-by might observe wedding parties spilling from the church or smell barbecued chicken and hamburgers as the parish responds to the hunger needs of island residents with its monthly Dinner Kitchen. The church dedicates itself to outreach in the community, annually tithing 10% of its pledged income to programs that serve children, the elderly, the environment, and areas of need, including food and housing.

The mission statement of Emmanuel Episcopal Church describes its role for the nearly 130 years of its existence: “As members of the historic village church, our mission is to love God and God’s creation with all our heart, soul, mind and strength and to love our neighbor as ourselves.”

Emmanuel Episcopal is a living history of its members and the milestones in their lives. The marble plaques behind the choir memorialize early settlers, including Charles Shattuck, who gave the land for the church. Stained glass windows on either side of the sanctuary commemorate the devotion of the first two clergymen, the Reverends Gray and Dickson, and the two chancel windows were a gift of Robert Moran, the builder of the mansion that became Rosario Resort.

The Bishop’s Chair came from a 17th century church in England that was bombed during World War II, and the hanging lamps date from the days of Sidney Gray, having come around Cape Horn. Of the seven lamps hanging in the sanctuary, the central one represents the Holy Spirit, while the other six are symbols of the gifts of wisdom, understanding, counsel, ghostly (or spiritual) strength, piety, and holy fear. The prie dieux also dates from the time of Sidney Gray, listed in his inventory of over 125 years ago.

The stained glass windows in the narthex are in memory of two young men who served as altar boys and were killed in action during the Vietnam War. The bell that signals the beginning of services and peals for weddings and tolls for deaths was cast in Holland. The exterior lanterns on either side of the front door were made in 1945 by Clarence Soule, parishioner and blacksmith. The altar rail was built in 2009 by master woodworker and parishioner Thomas Wendland. Nearly every item in the church—prayer books, altar linens, vessels, service books and candlesticks—has special meaning as a symbol of a cherished relationship with an individual, the church, and God.

The doors to Emmanuel Episcopal Church are open during office hours, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., Tuesday through Friday. We welcome and invite you to enter and feel the presence of God in this little church upon the rock and to attend a service if your time allows. Here, where the breezes of the sea caress the walls and the calls of gulls punctuate the liturgy, and where people of all walks of life and from all parts of the world have expressed their faith, may you, too, find peace. We also invite you to visit our church website, orcasepiscopal.org, for information on worship schedules and parish activities.

Emmanuel Episcopal Church history compiled on the occasion of the Centennial Celebration, 1985, by Marjorie Bevlin; updated and expanded by Margaret Payne, 2013.